PIM frameworks

Deborah Barreau

To understand how PIM is performed, Deborah Barreau tried to dismember it and so divided it in 5 sub- activities:[1]

- Acquisition: deciding which information will be included in information space, defining, la- belling and grouping information.

- Organization and Storage: classifying, naming, grouping and placing information for later retrieval.

- Maintenance: updating out-of-date information, backing up information, moving or deleting information from information space.

- Retrieval: process of finding information for reuse and • Output: visualizing the information space based on users’ needs and objectives.

Barreau's framework threats a PIM system as a monolithic system centered on a file hierarchy.

Richard Boardman

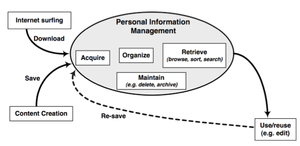

Barreau's classification of PIM activities was a basis for Richard Boardman’s classification. Boardman argued that updating information content cannot be a part of PIM, as it deals with content of information items. He also argued that visualizing is done by computers (not users) and that visualization is present in all sub-activities.[2] He describes four PIM sub-activities as:

- Acquisition: naming and/or (deciding of a) placement in information space.

- Organization: placing information items, renaming, moving and creating new folders.

- Maintenance: backing up and deleting information from information space.

- Retrieval: browsing, sorting and searching for information.

This framework focuses on a computer as a set of several PIM systems (software applications) that allow a user to manage a collection of personal information in a particular technological format

William Jones and James Teevan

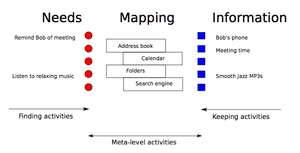

Jones and Teevan devided all PIM activities in three main groups that support our needs in correlation to information:

- Keeping activities: decisions focused on a single information item about the future needs and future availability.

- (Re)finding activities: driven by our needs for information in PSI.

- Meta-level activities: maintenance (composition and preservation) and organization (selection and implementation of a scheme) of the PIC within PSI, managing privacy, evaluating PSI, making sense of information and information distribution.

The first group of activities is focused on the flow from information to our needs and the second group on the flow from our needs to information. All other activities support both flows as can be seen in Figure 2.[3]

This framework is more general as Boardman's and Barreau's and include the whole users' personal information space

Authors also explain these activities in more detailes:

Information seeking: activities directed towards accessing information to satisfy our need or goals. Consider writing a paper: we have to find relevant papers of the subject and all activities involved in searching and finding these paper fall in this category.

Information keeping: decisions and actions about an information item currently in consideration that affect later retrieval. This simply means that we have to decide either to discard information or to keep in and how to keep it. Consider the above example of papers: we visit many web pages with papers and for each one we decide to leave it (discard it because it is not relevant or we think we will easily find it in the future), but some web pages are of great interest (for a paper) and we save them as web bookmarks, print them, save them in a special reference format (e.g. bibtex) ... These activities happen very often and focus is on one information item.

Refinding information: the process of finding information that has been seen before.

Information organizing: decisions and actions about information schema for a collection of information items. This means that we have to decide how to organize a personal information collection to make sense to us. Consider writing a paper: we have to organize references, have to decide on a format (e.g. Bibtex), decide on a software (e.g. BibDesk), decide how to name references (e.g. author's last name, year and first word of a title: jones2008personal, structure, tag, annotate ... These activities happen sporadically and their focus is on collection.

Information Maintaining: decisions and actions about composition and preservation of personal information collection. Consider references from example above: we have to decide which new items are going in a collection, which have leave it, how to back up the collection ... These activities preserve the state and nature of a collection to serve us. Focus is again on a collection.

Matjaž Kljun

Main article can be found here

This framework is based on Bordman's and it includes four PIM sub-activities: acquiring, organizing, maintaining and retrieving. But it does not impose strict borders between PIM activities; rather it presumes that PIM activities overlap (not only happen interchangeably).

Its starting point is on different acquisition types which influences all other activities. It tries to frame for example such issues: an email that is automatically acquired and placed in our inbox which is for example our personal information collection; is deleting this email a keeping activity as we process new email messages and decide which we will keep or discard; or is deleting maintaining as we decide which information stays in the collection.

Acquisition

Acquisition can happen in three different ways: created, received and found. And each of these three sources can be acquired in several of these modes:

We have a total control over manually acquired information which can be (re)named and/or placed in information environment based on our decisions at the time we decide. On the other hand, automatically acquired information piles up in a predefined place while we do not have a control over its acquisition. While semi-automatically acquired information still needs our action to be acquired but some actions (like naming and placing, time of acquisition) can be done without our intervention (e.g automatically by an application). |

Organization

| Users change organizational structure (even if only a small part) also during other activities and that many such small changes incrementally (while thinking and rethinking about small portions of the existing schema) change structure and organization of PICs and PSI. As such information organization overlaps with all other activities as can be seen in Figure 3. |

Maintenance

| Maintenance is performed to support future (maybe unknown) needs and tasks. Maintaining means to manage the organizational schema in such a way that information related to past tasks, for which it is assessed that it will not be needed any more, is moved out of the way and the organizational schema is organized in a way to support future tasks while it still has to support ongoing tasks. |

Consider two tasks:

- Lets get this desk organized as a sporadic activity in comparison to

- Daily organizing email inbox (moving, filing or deleting items).

Both tasks include organizing. But first one is about moving piles of papers from a desk to make place for new ones and to support other future PIM activities (in the long run). While the second task is more about supporting present PIM activities (not get overflown with email on a daily bases). Certainly it also supports future PIM but is more focused in the present.

a framework of keeping activities only

CEO model

http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1277989

http://www.cs.ubc.ca/~mike/master.pdf (pages 96, 109)

Notes

- ↑ Deborah Barreau, Context as a factor in personal information management systems, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 5/46, 1995

- ↑ Richard Boardman, 2004, Improving Tool Support for Personal Information Management, Doctoral dissertation, Imperial College, London

- ↑ William Jones and James Teevan, editors. Personal Information Management. University of Washington Press, 2007